How curiosity, creativity, and play can reshape your design process.

Most design advice tells you to optimize: work smarter, manage your time, refine your process. But what if the real unlock isn’t about optimizing, but about thinking more like a kindergartener?

In a world where creativity is more valuable than ever, many designers feel boxed in. Rigid processes, tight timelines, and pressure to get it right the first time can squeeze the life out of ideas. We forget that great work often starts with wandering, not planning. With trying, not knowing. With play, not performance.

This guide explores a different mindset, one inspired by kindergarten classrooms, where imagination, building, sharing, and reflection are the means by which learning occurs. Drawing from the work of MIT’s Mitchel Resnick, we’ll explore how his “Kindergarten Thinking” framework can help you approach design in a more open-minded way.

Part 1 / Rediscovering creativity: What kindergartners get right

Modern work is optimized for efficiency and rewards conformity and productivity, not imagination. But creativity needs something different: space to explore, permission to play, and room for curiosity to lead the way.

Mitchel Resnick, a researcher at the MIT Media Lab and creator of Scratch, believes the rest of life, not just school, should be more like kindergarten, not less. His philosophy, “Kindergarten Thinking,” advocates a learning approach centered on imagination, experimentation, and collaboration. Not a linear checklist, but a looping process of imagining, making, sharing, and reflecting.

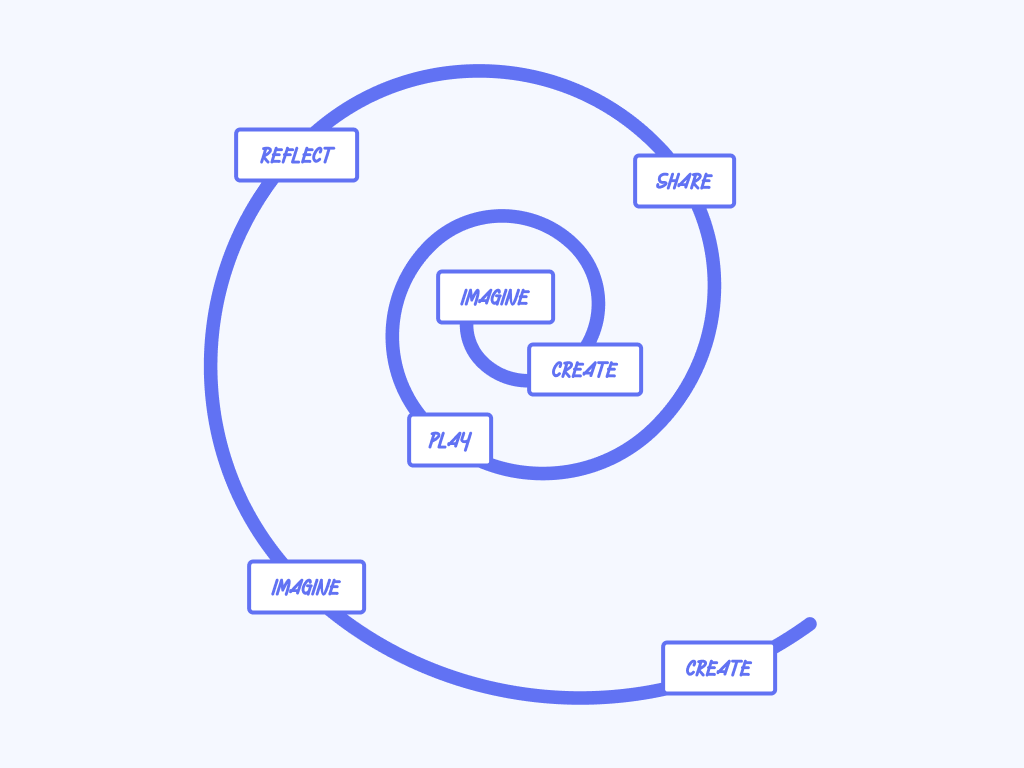

This is known as the spiral of creative learning. It starts with an idea, then takes shape through building or making. From there, playful tinkering opens up new possibilities. Sharing that work with others brings fresh feedback and perspectives. And reflection, asking what worked, what didn’t, and why, creates the momentum for another loop through the spiral.

Many creative people already work this way, looping through ideas and iterating as they go. But under pressure, it’s easy to stop trusting that instinct.

In contrast, most adult work culture prizes predictability over play. Deadlines, deliverables, and expectations can crowd out the space needed to explore. We skip the messy middle. We rush to results. But creativity lives in the chaos in between.

And that’s exactly when we need kindergarten thinking most.

The open, exploratory spirit of a good kindergarten classroom offers a powerful reminder: curiosity leads to discovery. Play reveals new paths. Collaboration makes ideas better. Reflection brings clarity.

Take a moment to reflect: When was the last time you felt truly curious while working on something? What was different about that experience? Did you have more space, more ownership, or fewer expectations? Did it feel a bit like play?

Chances are, your best ideas didn’t come from following a rigid brief. They emerged when you let yourself wander, tinker, and explore.

The best part? This mindset isn’t a one-off; it’s a habit you can build into everyday work. In Part 2, we’ll explore how.

Part 2 / How kindergarten thinking helps you design better

At the heart of kindergarten thinking are four core ingredients: projects, passion, peers, and play. Mitchel Resnick calls them the four Ps. They apply just as much to professional design teams as they do to five-year-olds with building blocks.

Projects, passion, peers, and play aren’t just for kids. They’re the building blocks of creative work at any level.

Let’s reframe each through the lens of creative work:

Projects

Kindergarten kids don’t learn by memorizing; they build things that matter to them. That’s where their focus, energy, and growth come from.

Designers are no different. Creative confidence grows when you’re working on something real. If the problem feels too abstract, disconnected from users or outcomes, it’s hard to care, and harder to push through uncertainty.

Real projects provide creative energy with a purpose. A user's need, a team's goal, and a side project; these are the containers that focus our effort.

Passion

Young kids chase what excites them. Designers should do the same, but with intent.

This isn’t only about following what feels fun, but fun can be a signal. It’s often the doorway into deeper curiosity and meaningful work. What keeps showing up in your thinking? What idea won’t leave you alone? Follow that thread.

That kind of engagement unlocks more creativity and often leads to better, more innovative ideas.

Peers

In kindergarten, kids create side-by-side. They borrow ideas, give feedback, and build in public. It’s a shared process. Not just collaboration, but co-creation.

That’s the essence of co-design: designing with others. It means involving peers early, valuing their input throughout, and shaping the outcome together.

Designers benefit from the same posture. Share before things are polished. Invite real input, not just a sign-off. Let teammates and stakeholders help shape the direction, rather than just responding to it.

When you open up your process like this, you don’t just get feedback, you get better ideas, faster. You create shared ownership. And you tap into the collective creativity of the group.

Play

Play is the engine. It’s how kids test limits, invent possibilities, and keep momentum going.

Importantly, they don’t dwell when something fails. If a block tower falls or a drawing doesn’t work out, they move on. They try something else. For them, it’s not failure, it’s just part of the process.

For designers, play means experimenting without pressure. It looks like quick sketches, working with an idea that doesn't immediately make sense, or throwing out the first five ideas to get to the sixth.

When we treat our work as something to explore, not prove, we create space for new directions to emerge. This process requires spending time on discovery.

A quick example

Let’s say, as the designer on a project, you received a brief with a clear problem and an implied solution. The expectation was to implement a refined version of what had already been scoped.

But instead of defaulting to what was assumed, you took a step back and asked, “What if?” That question opened up the space to explore. You imagined different possibilities and cast a wide net, brainstorming new ways to approach the problem.

By suspending the need to land on an answer immediately, you can uncover stronger, more creative, and user-focused directions that hadn’t been considered. It wasn’t about resisting the brief, but looking beyond it.

That shift, from accepting a solution to rethinking the question, can change the outcome entirely.

Kindergarten thinking isn’t a framework or method. It’s a posture. When you design in the spiral of creative learning, it is less about performance and more about exploration.

Part 3 / Design like a kindergartener: a mindset shift for modern makers

Imagine, create, play, share, reflect—then do it again.

Kindergarten thinking isn’t just a feel-good idea. It’s a practical mindset for creative work, especially in environments that prize output over exploration.

Mitchel Resnick’s spiral of creative learning gives us a model: imagine → create → play → share → reflect. Then repeat. It’s not linear. It’s cyclical. It welcomes being open to a path unknown, embracing failure, and rewards curiosity, treating each step as fuel for momentum, not a checkpoint to clear.

Designers already work in a loop: research, sketch, prototype, test, and revise. But too often, those loops feel like pressure to deliver, not permission to explore.

So what if you made space for imagination, experimentation, and reflection—not just when things go wrong, but by default?

Here are a few questions to consider:

- What’s something you’re curious about but haven’t explored, because it didn’t feel "productive"?

- What would happen if you treated your next idea like a toy or a sketch, not a deliverable?

- What if your next prototype were for your peers, not your stakeholders?

Try this: pick an idea you’ve been sitting on, something small, interesting, and maybe a little weird, and run it through a mini spiral.

- Imagine: Let yourself wonder. No prompt, no pressure. Just curiosity.

- Create: Make a quick version. A sketch, a messy draft, a working file.

- Play: Push it further. Break it, remix it, try something unexpected.

- Share: Show someone. Ask what they notice, not what they’d fix.

- Reflect: What surprised you? What did you learn? What might come next?

Then loop again.

At its core, this is what design has always been—and what it’s meant to be.

Kindergarten thinking doesn’t ask you to take your work less seriously. It asks you to make your process more open. Because when you bring imagination, curiosity, and play into your practice, you don’t just make better things, you become more creative, resilient, and alive in the work.

Creativity isn’t something you master once. It’s an ever-evolving work in progress.

And like the best kindergartens, your creative practice works best when it’s rooted in curiosity, guided by passion, shared with others, and open to play.

Kindergarten thinking means being open. Willing to try. Willing to wonder. Willing to learn by doing.

So the next time you feel stuck, stale, or boxed in, remember the spiral:

Imagine, create, play, share, reflect. Then do it again.

It’s not just a better way to design. It’s a better way to stay connected to why you started designing in the first place.